Evolution of Buddhism: Looking for Answers on the Silk Road

I traveled recently (May-June 2024) with a World Bank 1818 group of intrepid modern day “Silk Roaders” who recreated an itinerary that included several stops (once oasis centers) along the ancient Silk Route: Xi’an, Tianshui, Lanzhou, Dunhuang, and ending with Turpan and Urumqi in Xinjiang Province, after crossing parts of the Gobi and Taklamakan Deserts; other braver souls journeyed on to Kashgar.

I joined for many reasons: because the Middle Kingdom beckoned and who could resist, to meet likeminded fellow travelers, tread the path made famous by explorer Marco Polo (who may have exaggerated his exploits, say academics), and, chiefly, to discover why and how Buddhism evolved in the centuries following the death of the historical Buddha. It was all very adventurous and exciting; but would it deliver?

Background

Buddhism has a complex history spanning more than two millennia. Over time, its spiritual traditions have adapted to a range of geographical, social, and cultural circumstances, including war, invasion, and persecution.

Originating around the Kingdom of Magadha in northeastern India in the 5th century BCE, it is based on the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama and spread throughout central, east, and southeast Asia. In so doing, it evolved into a belief system that was quite different from the original. Importantly, it survived, even thrived. (1)

Spread of Buddhism on the Silk Road

Indian emperor Ashoka (268 to 232 BCE) of the Mauryan Dynasty, used his power to spread Buddhism. He famously renounced violence after the Kalinga War, one of the deadliest battles in Indian history, made Buddhism the state religion, and sent missionaries to neighboring countries. (2)

By the beginning of the Common Era, Buddhism followed the vast transcontinental network of overland routes known as the Silk Road into central Asia and China. It is widely believed that Indian monks traveled with merchant caravans to preach the new religion, entering China during the later Han period (206 BCE-220 CE).

Buddha’s rejection of the Hindu caste system (and of Brahmin priests who perpetuated that system) attracted followers. Unlike Hinduism, Buddhism did not have a negative view of trade and commerce, leading to merchants from the Vaisya caste converting to Buddhism. The concept of dana (or giving, charity) encouraged monks to ask for and receive donations from merchants. These donations helped build temples, dharamshalas (or monasteries), and rest stops on the Silk Road.

Trading centers along the caravan routes grew into large bustling multi-ethnic cities that provided a structure and system for Buddhism to travel east, helping it expand into a world religion with a diverse set of beliefs and practices. The Silk Road thus had a major impact on history, commerce, cultural exchange, and religious movement.

Back to India

In India, Hinduism experienced a powerful revival under the Gupta empire (320 to 550 CE). Threatened by Buddhism, orthodox Brahman priests touted the myth of the Buddha as an avatar of Vishnu; according to historian Wendy Doniger, this first appeared in the Vishnu Puranas (400-500 CE). By the 4th century, Hinduism had assimilated Buddhism (A.L. Basham, Indologist). I won’t repeat my theories of why I think Buddhism disappeared from India: see my earlier blog. More interesting is how and why it changed and flourished in China. (3,4)

During the reign of Chandragupta Maurya (322 to 297 BCE) — marked by a tolerance towards different faiths: Vedic and Brahmanical Hinduism, Jainism, Zoroastrianism, and Greek beliefs — Buddhism experienced its own short-lived resurgence in India. But it was a different kind of Buddhism that came back from China over the Silk Road, influenced by Taoist and Confucian elements as well as Zoroastrian fire worship and the Greek pantheon.

Ability to Adapt and Blend

China may have been receptive to Buddhism because it was a way to live one’s life, including addressing larger metaphysical questions of Karma, suffering, and death. It coexisted (sometimes peacefully, sometimes not) with Taoism and Confucianism. While there were anti-Buddhist movements, most rulers seemed to embrace the new faith.

Laypeople may have found Buddhism appealing because it challenged existing hierarchy and permitted all classes a role in spiritual practice; significantly, women were not excluded. Buddhism took on an essential Chinese character, blending with existing philosophies and folk tradition. As it became more inclusive, ancestor worship, family duty, and honoring one’s elders (existing in Brahmanical Hinduism) became an integral part of Chinese (or Han) Buddhism, as it came to be called.

A scholar I recently met said that Chinese spiritual practice was marked by a kind of “hodgepodge pluralism!” A professed atheist, he was amused that some of his friends recited mantras in Buddhist temples while also studying Taoist talismans, and practicing ancestor worship, Feng Shui, and qigong!

Change vs. Stasis — Female Buddha

In China, non-existence of a creator god (central to Indian Buddhism) diminished in importance while Mahayana became dominant; as time passed, Buddha and his Bodhisattvas were worshipped as gods. (5,6)

One might argue that, if a great religion remains static, it dies. Change could therefore be considered a positive. Change allows new modes of worship, new Bodhisattvas, and new ways to interpret Buddha, even as a woman.

While gender-fluidity might be shocking to a purist, it is more acceptable to those already praying to female deities. Worship of the female has a place in most traditions. Buddhism has relied on the worship of Bodhisattvas identified as female and vested with feminine attributes like compassion and nurturing.

It is generally agreed among Buddhist scholars that the Chinese figure Guanyin is the same as the one known in India as Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara. While Guanyin's history began in ancient India as a male figure, after two millennia in China, he was transformed from male to female and gained a new name.

Evolution of Guanyin in Art

Prior to the Song dynasty (960–1279 CE), Guanyin was always masculine. Later images, which displayed both genders, adhered to the Lotus Sutra (scriptures) where Avalokitesvara assumes any form. This tracks with ancient Brahmanical Hindu belief in Ardhanarishvar (or half man, half woman), a manifestation of the destroyer god, Shiva, representing male and female energies in the universe.

By the 12th century, Guanyin began to be interpreted as female: a mother goddess and patron of mothers. She is shown holding an infant to emphasize the relationship between the Bodhisattva, maternity, and birth. (7)

Ahimsa and its Impact on Vegetarianism

Gender was not the only change. The doctrine of ahimsa (or non-violence to all living things), once considered fundamental to Indian Buddhism, was also modified. How else to reconcile Buddhists with meat-eating, a practice that conservatives might censure? This too must be seen in the context of local traditions influencing beliefs.

Some Buddhists avoid eating meat because of Buddhism’s precept to “refrain from taking life;” others abstain based on the Mahayana sutras which forbid flesh consumption. Only in India are Buddhists strictly vegetarian. Elsewhere in the world, they are not, except monks and nuns or only on certain days of the week.

I recall being scolded by a Buddhist scholar during one of my long ago treks in Nepal. When I expressed surprise at local Terai (plains) people eating buffalo meat (doubly taboo as it’s related to the cow, sacred in South Asian faiths), he retorted, why would you deprive some of the poorest people in the world from consuming the cheapest form of protein? I was suitably rebuked!

Food habits are almost always shaped by availability and pricing and have very little to do with religion which must adapt to local custom and practice to survive!

Persecution of Buddhists

Buddhism is considered the oldest “foreign” religion in China and took over a century to become absorbed into Chinese culture. During the Tang dynasty, it became a major part of Chinese life and, although Tang emperors were usually Taoists, they favored Buddhism.

However, attitudes changed and, from the 5th to the 10th century, Buddhism faced persecution by four Chinese emperors; one of the worst of these campaigns was in 845 CE when Tang Emperor Wuzong, a Taoist, destroyed thousands of monasteries, forced monks and nuns into hiding, and seized monastery wealth and property. The emperor wanted to drive out “foreign” influence and appropriate war funds.

By then Buddhism had lost favor because monasteries had become a powerful force, monks did not pay taxes, and many young men were entering monastic life to avoid military service.

Buddhism also came into conflict with Confucian intellectuals who said it weakened existing social structures and loyalties (son to father, subject to ruler) by encouraging lay people to abandon their filial duty, renounce their families, and become monks and nuns. (8)

Despite these aberrations, Buddhism (for the most part) thrived among the Chinese population, particularly during the Song dynasty when it moved out of official state patronage and into mainstream life. Meanwhile, the government began to extend control over monasteries as well as the ordination and legal status of monks.

Reshaping the Culture

With its long history, Buddhism is considered the largest institutionalized religion in China. It has played an important role in shaping Chinese civilization and in influencing art, literature, and the prevailing culture.

During the Tang and Song periods, Buddhism contributed to painting and sculpture and advanced the development of printed books and religious architecture. Buddhist themes can be found in much of the period’s art and literature. Tang Empress Wu Zetian, who ruled from 660 to 705 CE, promoted Buddhist cave art, while portraying herself as a Bodhisattva.

Under Deng Xiaoping, who led China from 1978 to 1989, a revival of Buddhism took place when damaged temples and monasteries — that had been destroyed during the Cultural Revolution (1966 to 1976) — were restored. Monks are now allowed to be ordained and to practice. The current “sinicization” policy requires religious institutions to align their doctrines with Chinese culture and communist party leadership.

Laughing Buddha

In India, the Buddha was usually shown in painting and sculpture as an ascetic sitting cross-legged in deep meditation, radiating calm, with his hands in different mudras (or poses). As the religion spread, similar looking Buddhas were sculpted and painted with facial features changing from Gandhara Greek to Mathura Indian and adopting local facial characteristics as it spread eastwards. But perhaps the most radical change came with the Laughing Buddha, a significant departure from the classical Indian image of the slender meditative ascetic!

Laughing Buddhas may have originated from a Chinese folk deity, based on a 9th century wandering monk. An incarnation of Maitreya, the future Buddha, he is pot-bellied, heavy, bald, robe-clad, carrying a sack, prayer beads, and a beggar’s bowl. These statues are seen in temples, restaurants, gardens, and homes in China and southeast Asia, including Asian restaurants and homes in the U.S. Rubbing his belly is said to bring good luck! Laughing Buddha statues are now the most recognizable and popular Buddhist images in the world!

Conclusion

In China, Buddhism clearly took on the culture into which it migrated. From belief in Buddha’s divinity to a female Boddhisattva, changes in Ahimsa, acceptance of ancestor worship, and evolution of the Laughing Buddha, one could say that Han Buddhist practice has transformed the ancient purist version of Indian Buddhism into a more inclusive and pluralistic set of beliefs.

I’m not sure I found all the answers I was looking for but I learned a good deal from talking to smart and thoughtful guides, experts, scholars, and fellow travelers — both in western China and my week in Shanghai. It may take more journeys along the Silk Road to come up with definitive theories. Most importantly, I had fun in the process!

Footnotes

(1) Briefly, Buddha taught that dukkha (or grief, suffering) is unavoidable; that the samudaya (or cause) is tanha (or craving, desire) and that avidhya (or ignorance, misconception) can be ended by nirodha (or removal, letting go); also, by leading a moral and disciplined life and adopting the Eightfold Marg (or path) to navigate between extreme self-indulgence and extreme asceticism.

(2) The Kalinga War (262-261 BCE) was fought between the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka and the kingdom of Kalinga on the east coast of India in present-day Odisha state.

(3) Buddhist scholars regard it as heretical to even consider the Buddha as part of the dashavatar (10 incarnations of the Hindu preserver god, Vishnu)!

(4) http://luditravel.blogspot.com/2023/10/tree-serpent-early-buddhist-art-in.html

(5) Bodhisattvas or Buddhas-to-be are enlightened beings who choose to remain in the samsara (or cycle of Karmic births and deaths) to help others attain moksha (or freedom). They are revered for deferring their own parinirvana (or ultimate salvation) for the common good.

(6) Around the first century CE, Buddhism divided into two sects: Theravada or Hinayana (which spread to Sri Lanka and southeast Asia) regarded Buddha as a teacher, while Mahayana (which spread to China, Japan, and Tibet) claimed Buddha as divine. In general, Mahayana Buddhists follow the path of the Bodhisattva while Theravada Buddhists follow the path of the Arhat (or already enlightened person).

(7) The Jade Buddha Temple in Shanghai has a shrine to Guanyin.

(8) The concept of renouncing the material world through meditation and tapasya (also, tapas) or penance, is common to all South Asian religions: Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, and Sikhism.

References:

On Hinduism, Doniger, Wendy.

The Wonder That Was India: Vol. I & II, Basham, A.L.

Ancient China: Chinese Civilization from its Origins to the Tang Dynasty, Scarpari, Maurizio.

The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han (History of Imperial China), Lewis, Mark Edward.

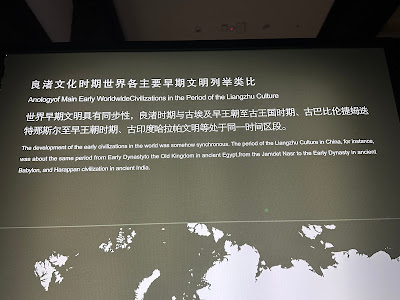

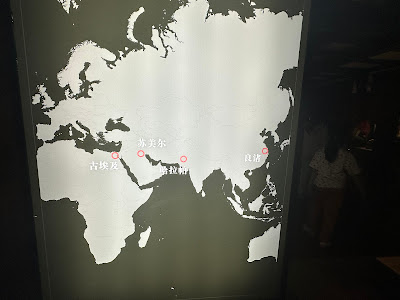

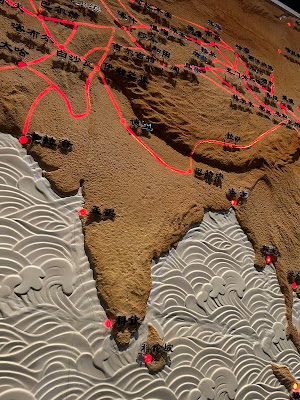

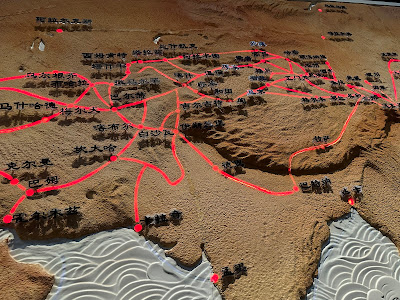

Source, Silk Road Maps and Video: Gansu Museum, Shaanxi History Museum

|

| Silk Road Map: network of transcontinental and maritime routes, Gansu Museum |

|

| Silk Road Map, Shaanxi History Museum |

|

| Silk Road Map, Shaanxi History Museum |

|

| Itinerary for Modern Day “Silk Roaders” (Wild China) |

|

| Guanyin at Jade Buddha Temple, Shanghai |

|

| Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, Mogao |

|

| Seated Buddha Gandhara style |

|

| Seated Buddha Mathura style |

|

| Buddha Image Mathura style |

|

| Ahimsa Symbol |

|

| Laughing Buddha |